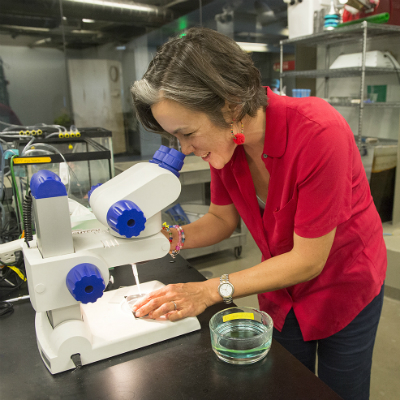

Kristina Yu, Ph.D. is the director of the Living Systems group at the Exploratorium, a public learning laboratory and science museum in San Francisco. The Living Systems Laboratory includes the Microscope Imaging Station, a facility that allows museum visitors to control research-grade microscopes to explore living biological samples and provides high-quality imagery for educators.

Kristina Yu, Ph.D. is the director of the Living Systems group at the Exploratorium, a public learning laboratory and science museum in San Francisco. The Living Systems Laboratory includes the Microscope Imaging Station, a facility that allows museum visitors to control research-grade microscopes to explore living biological samples and provides high-quality imagery for educators.

Through a Moore Foundation grant, Kristina and her team are developing a series of exhibits that will allow Exploratorium visitors to explore the amazing journey from a single cell to an adult organism through interactions with scientists, living specimens, real scientific tools and genomic data.

In this installment of Beyond the Lab, Kristina describes her unique ‘conductor’ role at the Exploratorium, and how being comfortable with not knowing helps us learn more about the natural world.

What inspired you to become a scientist/researcher?

My parents have undeveloped land in northern California near Clear Lake. When I was a kid, we spend most of our summers and weekends up there. It was very rural, and at the beginning there was no electricity or running water. This was pre-internet. We relied on the outdoors and a big stack of National Geographic magazines for entertainment. I was outside a lot with my sisters, but I also spent a lot of time reading National Geographic. I think this very early exposure to the breadth of the natural world, coupled with these amazing images and stories of discovery from all over the world, helped pique my interest in science.

When I was in grad school, I realized that depictions of scientific findings in the media were often inaccurate or highly sensationalized, and this fueled a desire to shift from basic research to science education.

What topics/areas/problems in science education are you most interested in?

At the Exploratorium, we think carefully about how to foster wonder, curiosity and question-asking about the world. I have a six-year old who is inquisitive and asks questions that seem very simple, but are very thought provoking. Often my only answer is, ‘I don’t know...let’s find out.’ Being comfortable with this state of not knowing, but really wanting to find out, has turned out to be great training for my work at the museum.

Developing museum exhibits that support visitors through scientific thought processes is a challenge that we are very interested in and are exploring with our project. Science isn’t a thing that people in white lab coats do in university laboratories. It’s a systematic way of thinking and a methodology you can apply to many aspects of your life.

Although I’m now in a project leadership role, I’m still able to do a bit of work in the lab, such as helping prepare a live sample that then goes into an exhibit prototype for example, which I find immensely gratifying. It’s also important to be on the museum floor, to simply observe. You can get hints from people’s body language when you've been successful: there’s this ‘OMG’ moment, or they run and get someone and bring them back to the exhibit to show them something. It’s very gratifying to see that kind of reaction to exhibits we're building.

How do your colleagues, mentors and students help you achieve your goals?

My high school biology teacher was an early mentor. I had an independent study period when he would let me explore the samples in his prep room, or he would pose questions that I’d have to investigate on my own. Later, I had a very supportive, thoughtful Ph.D. advisor who is definitely an enthusiastic, out-of-the-box thinker.

I now work with a fantastic project team at the Exploratorium. We share a common goal, and we all respect one another’s expertise in a way that I think is really wonderful. I’m constantly learning about many diverse disciplines that I would not have been exposed to had I stayed at the bench. I work with software engineers, graphic artists, multi-media developers, exhibit developers and science writers, to name a few, and I'm constantly in awe of the skills and expertise they bring to their work. A friend and colleague once said, ‘It’s like you’ve got this amazingly skilled group of musicians, and you’re the conductor. How do you support them in playing their best music together?’ I appreciate the skill and commitment of my colleagues every day that I’m at work.

We’ve also been fortunate that the scientific community has been very supportive of our work at the Exploratorium, and we’ve had many long, very fruitful relationships with researchers. They have been generous with time and ideas and often, materials. This is critically important because we can’t really do what we do without their support and participation.

What gets you going every day (besides coffee) and how do you stay motivated?

Watching visitors on the museum floor or visiting with my six-year old daughter is so rewarding. I've been at the museum for more than ten years, and too often I've run through the museum to conference rooms and not really taken the time to use certain exhibits. When I visit with my daughter, I'm here as a visitor and parent. I get to experience the world that we've built through her eyes and it's amazing! It's necessary, actually, for those of us who work in this field to take a moment, sit on a bench, watch visitors and kind of refresh as to why we're actually doing this in the first place.

We were prototyping an exhibit in which you stand on a scale and it tells you how many blood cells your body is producing while you're standing there. A visitor who tried it said, ‘I can't believe how busy my body is!’ That’s a very visceral epiphany, and so important in what we do. Spending time with your audience, not as a person who's working here, but just as an observer or visitor, can be really gratifying and helps refresh you as to why you're coming to work.

What are your greatest limitations/challenges in your role?

Some of the best ideas or rich trains of thought come from being outside of the workplace and giving yourself this wide variety of experience that is not your normal everyday existence. If I had more time in the day, I would love to give myself time and space to experience more new things, or explore new places, or just to think in solitude.

Whether it's being outside, or going to art museums or events, or travel, there are all these things that are happening in the world from which the spark of inspiration can come.

Learn more about Kristina’s work, and follow Exploratorium Lab (@explo_lab) on Twitter.

Message sent

Thank you for sharing.