Last April, I had the opportunity to visit Svalbard, an archipelago well above the Arctic Circle. Governed under the Svalbard Treaty of 1920 and officially a Norwegian territory, Svalbard hosts the highest latitude community worldwide, Ny-Ålesund, an international research station. Like the rest of the Arctic, Svalbard is changing quickly due to climate change. People who have lived there just a decade can attest that the spring now comes earlier, and the glaciers are retreating. While there, I saw tidal glaciers that, just ten years ago, had reached a kilometer further out to sea.

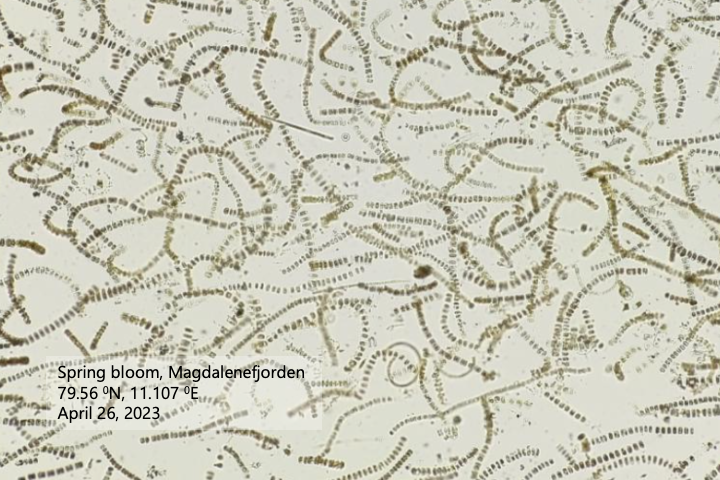

During my visit, I also witnessed the return of spring after the long and frigid Arctic winter – the sun doesn’t rise in Svalbard from late October to mid-February each year. Within three days of my arriving, the abundance of phytoplankton, or microscopic marine algae that form the base of ocean food webs, in the water skyrocketed. I brought a Planktoscope1 with me to document the spring bloom, and the evidence soon abounded.

Image: Diatoms collected in Magdalenefjorden on April 26, 2023. Picture captured by the PlanktoScope.

Soon, new seabird species appeared daily returning to their Svalbard summering habitats, including Black Guillemots, Black-legged Kittiwakes, Common Eiders, and Little Auks by the tens of thousands. I also saw resident walruses, polar bears, and harbor seals ready to feast on the revived Arctic abundance. And, though I didn’t see them, I knew that the blue, beluga, and fin whales were on their way to Svalbard from across the North Atlantic (blue and beluga) and breeding grounds off Morocco (fin).

Image: Flock of Little Auks flying. The circumpolar Arctic spring powers fly- and swim-ways totaling abundances of billions of individual animals that travel up and down the Pacific and Atlantic shores to reach the parts of the Arctic they use to feed, nest and mate.

Often, when we think about the largest animal migrations in the world, we think of the Serengeti’s wildebeest. Yet, the Arctic tern flies from Antarctica to the Arctic and back each year to avail itself of the incredible productivity reborn in each pole’s springtime. And, the Bay Area celebrates the return of the grey whales to our shores each spring as they move between their calving grounds in the Gulf of California to their summer feeding and birthing grounds in the Arctic’s Chukchi and Beaufort seas.

Like other rich areas in the Chukchi and Beaufort seas above Alaska and Canada, the waters surrounding Svalbard are a hotspot of productivity and biodiversity. Every summer, more than two hundred bird species and twenty marine mammal species travel here to gorge on the zooplankton and fish supported by the annual spring bloom.

But there are real concerns about the ability of Svalbard’s waters to remain a critical destination for these animals. In late 2023, the Norwegian Parliament passed a law to allow seabed mining off the western coast of Svalbard, close to the areas I got to experience firsthand last year. If seabed mining occurs, the pollution and noise caused by the drilling equipment and ships will harm the pristine area. Fortunately, the outcry against Norway’s decision has been loud, and there are signs that Norway is rethinking its decision.

Climate change could also affect the ability of Svalbard’s ocean ecosystems to provide nutrient-dense sources of food in the spring to migrating birds and marine mammals. Arctic oceanographers and ecologists fear that the earlier timing of the annual break up of sea ice could cause a disconnect between the spring bloom in phytoplankton and the emergence of zooplankton that consume them. As a result, the energy fixed by the phytoplankton could sink to the seafloor instead of moving up to the higher levels of the food web, to the fish, seabirds, and marine mammals.

The overall reduction in sea ice could also imperil the incredible productivity of Arctic marine ecosystems. With the extent of sea ice declining, the phytoplankton blooms associated with the edges of sea ice will shift northward and ultimately may decline. Yet, other vital Arctic habitats will remain highly productive, including areas of upwelling associated with seamounts and undersea ridges and coastal areas near river mouths.

The Marine Conservation Initiative supports work to protect the resilience of the North American Arctic Ocean so it can continue to support healthy ecosystems and sustainable fisheries. Implementing a network of protected areas in the Arctic Ocean is necessary to safeguard the most important habitats for biodiversity, including those that will continue to support enormous blooms of phytoplankton in warmer seas.

Climate change demands that we work at a larger scale than before. The rate at which the Arctic is changing makes it a tenuous assumption that we can protect functioning ocean ecosystems just by reducing localized threats with individual protected areas. Because of climate change, many populations will move, and ecosystems will be reorganized. Local conservation efforts (i.e., protecting one area) will make the most difference when there are many other protected areas in a network spanning a seascape. This is because of “rescue effects,” where, for example, the ability of animals to move between protected areas that safeguard their most important habitats supports the stability of their population.2

Removing other man-made threats to Arctic seas also will support ecosystem resilience to climate change. As the Arctic warms, a network of protected areas spanning a seascape in which fishing, shipping, and offshore development impacts are mitigated will be the best way to safeguard the Arctic’s valuable marine habitats for current resident and migratory species, as well as for the more temperate species whose ranges are shifting northward, like salmon.

Bearing witness to Svalbard’s spring bloom and welcoming home of seabirds that had traveled from far south grounded me again in the remarkable emergent abundance of the Arctic. The Marine Conservation Initiative is proud to have helped protect parts of the North American Arctic so that they, too, can continue to serve as essential habitats to the incredible migratory animals returning home to the Arctic each spring by way of the Bay Area. It is our goal that future generations will also experience this spectacular display of animal migration and abundant life – from the phytoplankton all the way up to the bowheads – in the Arctic.

Mary Turnipseed is a program officer with the Moore Foundation’s Marine Conservation Initiative

1 Former Wild Salmon Ecosystem Initiative Program Officer Michael Mehta Webster repurposed this term to describe the processes that turn on to help species, populations, and organizations adapt to environmental changes. Webster, Michael Mehta. “The Rescue Effect: The Key to Saving Life on Earth.” Timber Press, 2022.

2 The PlanktoScope is a small, digital microscope that enables scientists and citizen scientists to study and image plankton. The development of the PlanktoScope was supported by Grant #5762. Dr. Ajit Subramanian, a research professor at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and former Science team staff, lent me the PlanktoScope to collect in situ data for his lab to correlate with satellite observations.

Message sent

Thank you for sharing.