The most cost-effective way to combat climate change is to protect nature.

The first time I visited an Asháninka community in the Peruvian Amazon I realized how important it was to understand climate cues to survive. The dry season was the time to look for turtle eggs in the river sandbanks and start preparing the land for cultivation. The rainy season was the best time to gather wild fruit, honey and travel farther using canoes. My Ashaninka friend Rosa taught me how to harvest manioc and prepare it to cook in the hearth. It was joyful to hear my friends recognize the sounds of different birds that announced the changing of the seasons.

Today, those climate cues are not that reliable anymore.

We just went through the hottest summer in the north, and fires are raging in the Amazon region. The race to grab undesignated lands, the expansion of commercial agriculture and timber extraction, at the expense of cutting large areas of natural forest, have had a deep impact on nature and the livelihood of small landholders like the Asháninka. All these actions contribute to climate change.

There is evidence that modern humans evolved around 300 thousand years ago in Africa, and that humans have been present in the Americas for about 40 thousand years. It is fascinating to see how over these millennia humans, through cooperation and solidarity, developed solutions for their survival.

First, the agricultural revolution allowed humans to become sedentary and abandon their hunter-gatherer ways. Then, the industrial revolution provided solutions to economic growth; even though it had high social costs in most places. In general, nature seemed to provide unlimited resources and was taken for granted. Coal provided energy and the discovery of hydrocarbons supplied energy that fueled even more progress. The economic cost of using nature for development has not been fully considered until recently, and hopefully it is not too late.

A call for 70% protection in Amazonia

During my lifetime the human population has more than doubled: from about 3.5 billion to 7.98 billion. At a rapid pace, our planet is becoming more crowded with humans that need more natural resources, and we have nowhere else to move. Now we know enough to understand that the use of fossil fuels generates climate change and the loss of natural ecosystems which can mitigate climate change. We need to take care of nature through cooperation and community building to avoid triggering the collapse of natural ecosystems. Not just for the benefit of us humans, but also for the benefit of all living creatures that share this planet with us.

Because nature is under threat, the global community, through international agreements, has determined to work towards the goal of conserving 30 percent of terrestrial and marine habitat by the year 2030. The 30x30 approach is a goal for the whole planet. Some countries that are highly developed don’t have 30 percent of nature to conserve while others do have a lot more.

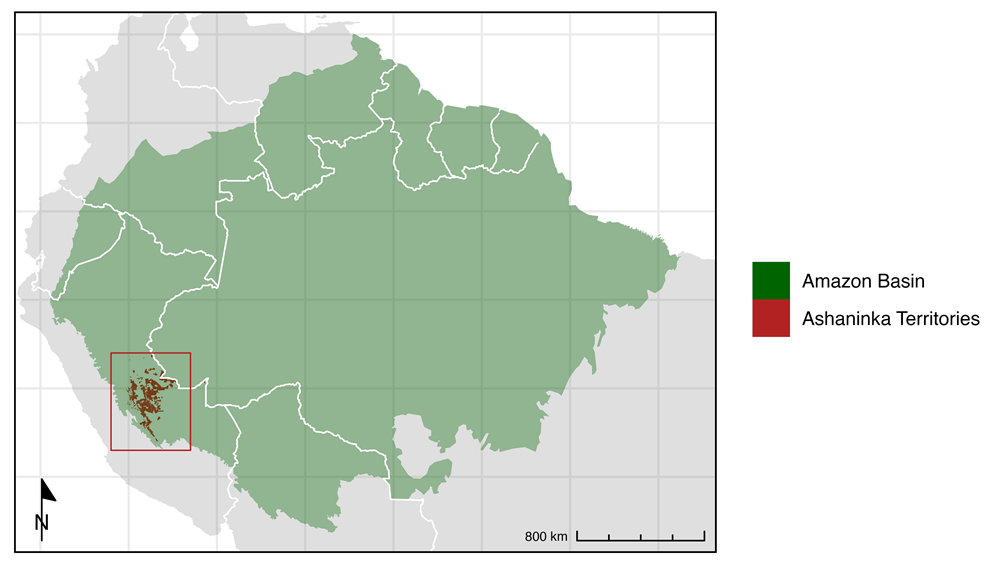

IMAGE: Map of the Amazon biogeographic region and the Indigenous territories map that was created using the Amazonian Georeferenced Socioenvironmental Information Network (RAISG). Map credit: Michael Esbach.

When we think of Amazonia (eight countries and one territory) we cannot settle for conserving only 30 percent. We need to conserve and manage at least 70 percent of the Amazon biome in sustainable ways if we are to avoid a planetary tipping point with consequent loss of carbon sequestration: from rich tropical forests to poor savanna ecosystems.

The good news is that thanks to the work of governments and civil society coalitions, nearly 50 percent of the Amazon region is already under some type of conservation, either in the form of protected areas or collective lands managed by Indigenous peoples and local communities. For example, the Asháninka Indigenous people in Peru, who currently live in about 600 different communities in a fragmented territory, are successfully co-managing a Communal Reserve in the eastern slopes of the Andes mountains that is next to the Otishi National Park in the headwaters of the Amazon.

The cooperation between those who manage protected areas and those who live in Indigenous territories is essential to ensuring the durability of conservation outcomes and securing livelihoods.

The challenge we face in Amazonia to get to the 70 percent conservation target is two-fold. One is to sustain the gains and enforce effective management in the areas that have been designated for conservation (roughly 50 percent of the Amazon biome); and two, is to add at least 20 percent more of the Andes-Amazon territory under effective management.

The role of community and governance

Certainly, the objective is not just to have more protected areas, but to focus on improving the management conditions of land and freshwater ecosystems. We know what we need to do, and we have identified different pathways to get there. The first one is to support civil society organizations to make sure that undesignated public lands become conservation areas and Indigenous territories. At this time, political conditions in Brazil and Colombia are relatively favorable to advance this objective. It is more challenging in other countries where government agencies dedicated to environmental causes have been weakened to encourage economic growth with insufficient environmental safeguards.

Amazonia needs to be managed as one integrated system if we are to protect its ecological function. For example the recent announcement of the new Routes of Integration program in South America, which will make available about US$10 billion over the next three years for infrastructure projects to open routes of trade, needs to be watched closely so that it incorporates the necessary safeguards to avoid ecological fragmentation and the influx of new economic activities that may produce deforestation. This initiative will transform the economic landscape by more easily connecting the Amazon to the Pacific coast and lowering barriers to trade with Asian countries.

Nevertheless, I still have hope that we can find solutions to save our planet in a timely manner.

Good governance is at the heart of this solution, and it is positive tipping points that can accelerate the changes we need. Positive tipping points refer to changes that push systems toward more sustainable pathways, potentially reversing harmful trends. These solutions recognize the long-term consequences of key interventions on the ecosystems and societies. Coalitions that have been built carefully through cooperation have a higher chance of coming up with sound solutions that will help us preserve Amazonia. When an infrastructure project is being proposed, particularly in fragile ecosystems, there are many questions to explore. At minimum, we need to ask: Who will win and who will lose? How have environmental conditions, justice and social equity been factored into the equation to decide to invest in the project? Who has been consulted and engaged in the decision making?

Certainly, no one would like to repeat the mistakes of building a dam like Belo Monte in Xingu, Brazil. The construction displaced many Indigenous people while destroying the social cohesion that existed before the dam; also, now there is not enough water to make the dam fully operational.

Environmental conservation is not a neutral endeavor: We aim to listen and to give voice to those who are closer to the ground. Those who have thought of the practical solutions to achieving sustainable livelihoods and who will be most affected by decisions that take place in faraway cities. We need to change the narrative of gloom-and-doom and support the ingenuity of local people to pursue innovative solutions through cooperation and community building.

My friend Rosa taught me about more than harvesting manioc. She taught me to recognize climate cues and the importance of collaboration and solidarity for survival. We bartered manioc for other products, and we organized ourselves to work on different agricultural fields in a reciprocity regime. To be open to collaborating and building alliances are lessons that we all need to learn and practice as we aim to conserve Amazonia and our planet Earth.

Avecita Chicchón, Ph.D., is an anthropologist and leads the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation’s Andes-Amazon Initiative, which aims to secure the biodiversity and climatic function of the Amazon biome.

Image above: From right to left in the photo are Rosa Garcia, Avecita Chicchon, Rosa’s daughter China and a visitor from a different community who joined Rosa and Avecita on their way to harvest manioc. The photo was taken in 1983 by Marisol Molestina.

Banner image: Pipini River in Peru, credit Mongabay with an overlay of the Amazon biogeographic region and the Indigenous territories map that was created using the Amazonian Georeferenced Socioenvironmental Information Network (RAISG). Map credit: Michael Esbach.

Message sent

Thank you for sharing.