With great sadness, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation announces the passing of our founder, Gordon Moore.

With his characteristic humility and word economy, Gordon Moore once wrote “my career as an entrepreneur happened quite by accident.” A brilliant scientist, business leader and philanthropist, Gordon co-founded and led two pioneering technology enterprises, Fairchild Semiconductor and Intel, and, with his wife, Betty, created one of the largest private grantmaking foundations in the U.S., the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

He may argue that his career as an entrepreneur happened by accident, but his world-changing contributions did not. Never one to trumpet his own accomplishments, Gordon wasn’t able to dissuade others from celebrating his wide and long-reaching legacy: the revolutionary technologies and breakthroughs, a long and generous history of philanthropy, and the very culture of experimentation, invention and relentless progress that now defines Silicon Valley.

It took decades for Gordon to be able to speak with a straight face of his eponymous “Moore’s Law,” the prophetic 1965 observation that became a cornerstone principle of innovation and driving force for the exponential pace of technological progress in the modern world. Gordon later observed that he had looked it up and was pleasantly surprised to find more references on the internet to “Moore’s Law” than to “Murphy’s Law.”

Dubbed a “quiet revolutionary” by his biographers, Gordon always worked in the absence of any pretense or desire for recognition, driven instead by an exceptional curiosity, generosity and unassuming commitment to hard work.

Gordon Moore

Gordon was always a visionary. Even at the start of his career, he keenly recognized the impact that the technologies he was developing would have on the world. And at an industry event in 1979, he told an Intel audience: “We are bringing about the next great revolution in the history of mankind — the transition to the electronic age.” (Moore’s Law, Thackray, Brock and Jones).

Although Gordon was reluctant to spotlight his own contributions, his biographers have been less reticent about attribution. Gordon is simply, they argue, “the most important thinker and doer in the story of silicon electronics.”

A pioneering start

A fifth generation Californian, Gordon was born in San Francisco in 1929. The son of the local chief deputy sheriff, he grew up in Pescadero, a small coastal community in San Mateo County that had been home to his family since the mid-nineteenth century.

He loved to fish in his neighborhood creek and to experiment with chemicals and “make explosives on a small production basis” behind the house. From an early age, Gordon had a passion for the natural world, science and experimentation, and he pursued that with a bright inquisitiveness, appreciation and sense of gratitude that would last a lifetime and become guideposts for his philanthropy.

Fishing and exploring Pescadero’s untrammeled wilds as a child and venturing to Baja and Costa Rica and even farther afield in later years offered a baseline that illustrated environmental changes brought by development and mass tourism, too often not for the better.

Always an acute observer, this helped instill in Gordon a concern and abiding interest in conserving nature for future generations, in the San Francisco Bay Area and around the world. “We see the wild places of only decades ago being changed to golf courses and resort hotels, and do not think that the whole world should go that way,” he reflected to the Chronicle of Philanthropy in 2002. “I hope we will really make a difference, long term (i.e., 10,000 years).”

Gordon met his greatest love and fellow outdoor adventurer, Betty, in 1947 at a student conference at the Monterey Peninsula’s seaside Asilomar conference center. When the two weren’t fishing the nearby streams — they loved finding remote spots to enjoy being outdoors — Gordon spent his vacations working for a cement company and building his college fund.

By 1950, after transferring to the University of California at Berkeley from San Jose State University, Gordon had earned his bachelor’s degree in chemistry. He and Betty were married that same year at a small church in Santa Clara, and set out together for Pasadena, where he was awarded his Ph.D. in chemistry from the California Institute of Technology in 1954.

After graduating from Caltech, Gordon moved east for a job in research with the Applied Physics Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University. In early 1956, he was recruited west again by William Shockley, the soon-to-be Nobel Laureate who had, with his team at Bell Labs, invented the transistor. By 1957, Shockley’s abrasive management approach and fluid direction for Shockley Semiconductor prompted Gordon and seven of his colleagues to exit the company and form Fairchild Semiconductor.

Fairchild

At the helm of research and development at Fairchild, Gordon used his ingenuity to help create and manufacture silicon transistors and then produce a complete circuit of planar transistors on a single piece of silicon: the world’s first microchip. While Sputnik had just been launched into space, demand for silicon transistors skyrocketed as the U.S. rushed to propel its own space program forward, and Fairchild had become one of the shining stars of the electronics industry.

As Fairchild soared, Gordon’s team expanded to hundreds of researchers. The company was developing new technologies at a rapid rate, and Fairchild employees began leaving to create their own businesses. “Every time we came up with a new idea, we spawned two or three companies trying to exploit it,” Gordon reflected.

These “Fairchildren” included offshoots like Signetics, General Micro Electronics, Molectro, Four-Phase Systems — and, in 1968, Intel.

Moore’s Law and the importance of investment in science

Three years earlier, in 1965, Electronics magazine approached Gordon to ask if he would contribute an article on the future of electronics. In “Cramming More Components onto Integrated Circuits,” Gordon predicted that transistors’ cost would decrease at an exponential rate as the number on each silicon chip doubled annually.

“I never expected my extrapolation to be very precise,” Gordon said later. “However, over the next ten years, as I plotted new data points, they actually scattered closely along my extrapolated curve” (“Understanding Moore’s Law: Four Decades of Innovation” Edited by David C. Brock). In 1975, Gordon updated his prediction, by now recognized as “Moore’s Law,” anticipating that the doubling would happen every two years for the coming decade.

By the 50th anniversary of Moore’s Law in 2015, Intel estimated that the pace of innovation engendered by Moore’s Law had ushered in some $3 trillion in additional value to the U.S. gross domestic product over the prior 20 years. Moore’s Law had become the cornerstone of the semiconductor industry, and of the constantly evolving technologies that depend on it.

Critical to that engine of growth had been U.S. investment in basic research and STEM education, ten percent of the U.S. Federal Budget in 1968. By 2015, however, that had been reduced to a mere four percent. To Gordon, investment in discovery-driven science was another key impetus behind creating the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation in 2000, especially in the context of a widening funding gap for something he recognized as critical to human progress.

Intel

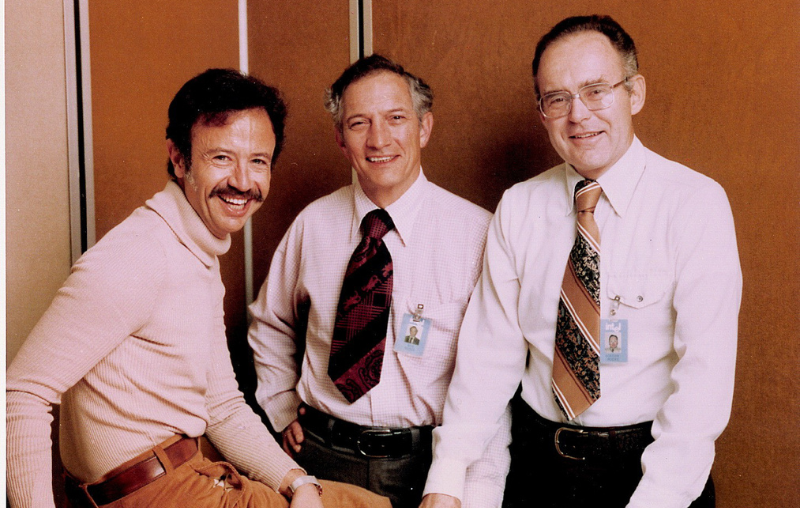

Andy Grove, Robert Noyce, and Gordon Moore

The most famous of the “Fairchildren,” Intel (for “Integrated Electronics”), was created in July 1968. Having left Fairchild Semiconductor and with financing help from Arthur Rock, Gordon and Robert Noyce invested $250,000 each in their new co-founded enterprise and raised another $2.5 million. Their first hire was Andy Grove.

Later billed as the “Intel Trinity” by Silicon Valley author Michael Malone, the three together built a company that, by 1971, had brought to market the first microprocessor, and by 1991, become the world’s largest semiconductor company.

Gordon became Intel’s president and chief executive officer in 1975. Four years later, he was elected chairman and chief executive. He became chairman emeritus in 1997, and retired in 2006.

Under Gordon’s leadership, Intel became the world's highest valued semiconductor chip maker. But Intel also helped establish Silicon Valley’s culture and ethos, offering stock incentives for employees and structured as a meritocracy that eschewed bureaucracy and rewarded innovation, loyalty and the entrepreneurial spirit.

A celebrated man

For his pioneering contributions, Gordon was recognized with myriad honors. Among them are the National Medal of Technology from President George H. W. Bush in 1990, and the nation's highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, from President George W. Bush in 2002.

Gordon served as a member of the board of directors of Conservation International and Gilead Sciences, Inc., and was a member of the National Academy of Engineering, a Fellow of the Royal Society of Engineers, and a Fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. He also served as chairman of the Board of Trustees of the California Institute of Technology from 1995 until the beginning of 2001, when he continued as a Life Trustee.

A notable philanthropist

Gordon and Betty Moore

Intel’s success made the Moores billionaires, but they never lost touch with their small-town pragmatism or unassuming roots. The financial windfall made them even more focused on giving back to society, to try, as they expressed, to make the world a better place for their children and their children’s children. Long before signing the Giving Pledge in 2012, Gordon and Betty had already given more than half of their assets to charitable causes. In 2017, they were recognized as California’s most generous philanthropists.

Beginning with individual gifts, many of them anonymous, then forming the Moore Family Foundation, and eventually, in 2000, creating the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation “to create positive outcomes for future generations,” Gordon and Betty have maintained a focus across their philanthropic endeavors on supporting universities, hospitals and other nonprofit organizations working in environmental conservation, science, patient care and the San Francisco Bay Area.

“We thought we had an opportunity to make a significant impact on the world,” Gordon once reflected. “And really that is what was attractive. To do something permanent and hopefully on a large scale.”

In 2015, he and Betty wrote their Statement of Founders’ Intent to capture and immortalize their hopes and expectations for their philanthropy. “Betty and I established the Foundation because we believe it can make a significant and positive impact in the world,” Gordon wrote. “We want the Foundation to tackle large, important issues at a scale where it can achieve significant and measurable impacts.”

But the man whose philanthropy would, he hoped, change the world for the better on a grand, meaningful scale — and whose observation of technological progress became “law” — also wrote this philanthropic guidance with characteristic humility, and just a touch of ironic self-deprecation: “Since it is impossible to predict the future with any certainty, the guidance cannot be very specific.”

Reflecting on the contrast between the Moores’ view of their own importance with Gordon’s aspirations for his scientific and philanthropic endeavors, Moore Foundation President Harvey Fineberg observed, “There is nothing ostentatious or extravagant in the way they live their lives. Yet, there is a grandness and inspirational quality in their belief in the improvability of the human condition.”

A humble man

Gordon laughing during the celebration of Moore's Law 50th anniversary

One evening in 2015, Intel and the Moore Foundation hosted a celebration at San Francisco’s Exploratorium to mark the 50th anniversary of Moore’s Law. During an interview at the event, Gordon was asked what he had learned from his legendary observation. With that same humble wit, he answered: “Well, once I made a successful prediction, I avoided making another.”

*Contributors include Tom Waldrop and Intel Communications.

Message sent

Thank you for sharing.