A growing number of Americans are living with serious illness and complex medical issues. This might include someone who has both heart disease and diabetes and also experiences early signs of memory loss. It is estimated that at least 80 percent of adults 65 years of age and older have at least one chronic condition and at least 68 percent have two or more chronic conditions. These people are not necessarily at the end of life but are in the last phase of life. This last phase can last for several years and has people experiencing a slow decline in their health over time. Unfortunately, many people are not taking the necessary steps to get ready for this phase of life. These steps include saving enough money, making living arrangements, determining who might care for them when they need help with daily living activities, and articulating what they want in their medical care and how they want to live in this last phase of life.

A new report Serious Illness in Late-Life: The Public’s Views and Experiences, explores people’s expectations about later life and efforts they’ve taken to plan for the event they become seriously ill. As part of our work in serious illness care, we worked with the Kaiser Family Foundation to conduct a national survey to better understand how people view and experience serious illness. The survey included interviews with about 1,000 adults who are either personally age 65 or older living with a serious illness, or have a family member who is or was before they recently died. We hope this survey can serve as a baseline for future surveys that measure how public attitudes and experiences about serious illness care change over time.

A few findings from the survey stood out for us and relates to the work we are doing to improve the experience and outcomes of patient care:

Steps are not being taken to plan for serious illness care in late life

The national survey finds that while the general public acknowledges that people typically die after a slow decline in health, and that there are known issues that can arise from serious illness, many people are not taking measures to plan for this situation. An important step to increasing preparation for this last phase of life is to increase knowledge of serious illness issues. To help with this, we also support Kaiser Family Foundation to report on health policy, medical practice and social issues regarding serious illness. This news is produced by Kaiser Health News and distributed through its regional and national media partners.

Training for family caregivers remains a need

The report, not surprisingly, also found that training provided to family members caring for someone with serious illness varies. Almost 40 percent of family caregivers say they were not well trained, or not trained at all, while a little over 60 percent say they were somewhat or very well trained in providing tasks. These tasks might include how to move someone safely, how to recognize signs of pain or distress and how to administer medications.

Recognizing the importance of challenges faced by family caregivers, and the need to provide more training to people caring for loved ones, we launched the Family Caregiving Institute at the Betty Irene Moore School of Nursing at University of California, Davis. Part of this grant supports the creation of a suite of materials for families to promote safety and quality, plus the development of learning modules for health professionals to engage more effectively with diverse caregivers.

Documentation of wishes for health care is spotty

Some encouraging statistics in the report show that a majority of people (87 percent) say it is very important to have a person’s medical wishes written down. Also, many report having conversations with a spouse, parent, child or other loved one about their wishes: more than half say they’ve had a serious conversation with a loved one about who will make medical decisions if they can no longer do so on their own (62 percent) or about their wishes for medical care if they become seriously ill (54 percent).

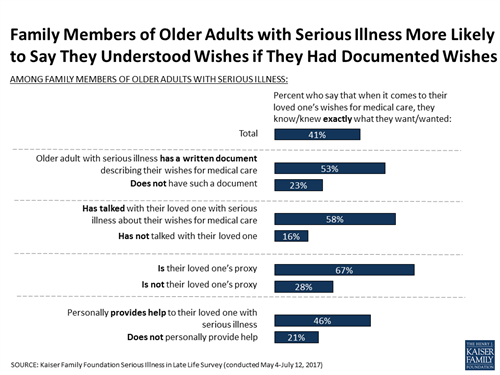

Yet, the kinds of conversations people are having frequently do not include what a person would need to have a good quality of life while seriously ill (38 percent), how they would pay for health care and other support they might need (36 percent) and where they would live if they’re no longer able to live independently (34 percent). Moreover, despite saying it is very important to write down their medical wishes, people are not doing so. Just a third of the public (34 percent) say they have a written document that describes their wishes for medical care if they became seriously ill, such as the types of treatments they would or would not want to receive. The survey found that, for older adults with serious illness, those with documents outlining their wishes for care are more likely to say their wishes have been followed, and nearly all family members who have referred to these documents say they have been helpful in making decisions about their loved one’s care.

Part of our work is aimed at helping people have substantive, clear conversations about the kind of care they want and what a good quality of life means to them, and then documenting these preferences. We are supporting The Conversation Project and the University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine to develop easy-to-use tools to help people have these conversations and to document their wishes in writing.

Not surprisingly, attitudes and behaviors vary across ethnic and cultural groups. In recognition of these differences, work by The Conversation Project also includes support for activities to engage with faith communities, with a focus on minority congregations, to bring conversations around end-of-life preferences to their constituents and to encourage completion of advance care documents.

Most people have not had conversations about their wishes with medical providers

Doctors and other medical providers can play an important role in helping people fulfill their wishes for medical care if they become seriously ill, however relatively few say they’ve talked to a medical provider about who would make decisions for them (23 percent), what sort of medical care they would want (18 percent) or where they would like to receive care if they became seriously ill (11 percent). Older people and people in fair or poor health are more likely to report having these types of conversations with a doctor, but still just about half of older people say they’ve talked about any of these issues.

To help clinicians feel comfortable and well-equipped to have these important conversations with their patients, we are supporting VitalTalk, Atul Gawande’s Ariadne Labs and Respecting Choices to expand their communications skills training programs. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, through its Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, is working specifically on improving communications skills of primary care physicians providing palliative, or comfort, care for people with dementia.

What’s ahead

We intend to use the results from this survey, and our ongoing work, including what high-quality care in the community should look like, to help refine our philanthropic activities so that we can have a lasting impact. The last phase of life will touch all of us and the better prepared we can be, the better experiences we, and our loved ones, can have.

Message sent

Thank you for sharing.