[Image] Kakani Katija. Credit: Todd Walsh © MBARI

[Image] Kakani Katija. Credit: Todd Walsh © MBARI

Kakani Katija is a principal engineer and lead of the

Bioinspiration Lab

at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) in California. The Bioinspiration Lab develops approaches and technologies to explore the ocean, and the Moore Foundation has supported her team’s work to develop

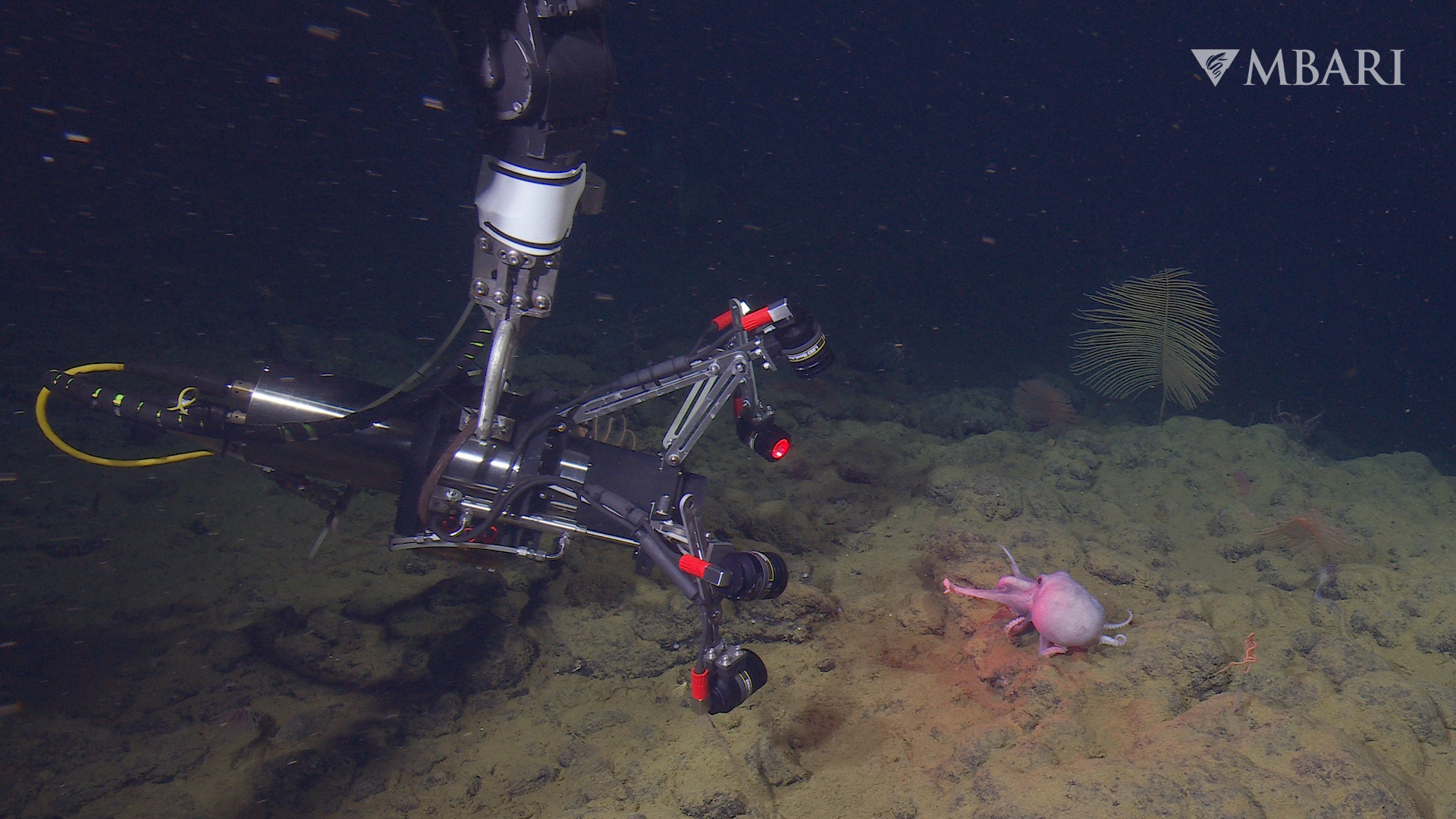

EyeRIS, an underwater optical imaging system capable of visualizing and measuring fluid motion, particles, and living organisms in three dimensions. EyeRIS uses plenoptic imaging, which functions like an insect’s compound eye. In August 2025, the MBARI team released

new research

around integrating EyeRIS into a remotely operated vehicle to observe and study the movement of deep-sea octopuses off the coast of California. The research has the potential to be applied towards advancing bioinspired engineering and designing new robots.

In this edition of Beyond the Lab, Kakani discusses her research, some of the most exciting moments of her career, and passes on advice to aspiring researchers.

What made you want to become a researcher in the first place?

I started out with an interest in sports journalism because I was an athlete and loved writing and at the time, the people who looked like me were in those kinds of positions. In my first year of college, I made the mistake of registering for chemistry, calculus, and physics and did very poorly for the first time in my life. Since I’m a very competitive person, I decided I wasn’t going to let that happen and ended up performing better, enjoying it, and learning about new opportunities. I didn’t really know that research was a career path, but I was fortunate to have mentors who saw my potential and guided me.

What have been some of your sources of inspiration throughout your journey?

My academic journey has not been a straight line, but my inspiration comes down to the animals in the ocean and how little we know about them.

My background is in aerospace engineering, and I was originally interested in the field because of the potential to discover new life and the fact that you could put minds together to create incredible technologies to answer questions about the universe. It wasn’t until I went to graduate school and started ocean-related research did I realize that there is still a lot left to discover and understand on our planet. There is so much about the ocean that is unknown to us, and that inspired me to think about how to close those gaps and create approaches or technologies to observe and understand ocean life. There’s a lot we could learn and benefit from in fields such as bioinspired design.

How would you describe the types of problems that you and your colleagues are most focused on solving?

Our group is called the Bioinspiration Lab, and we’re really focused on the technologies we need to observe and understand life in a very difficult to access place like the deep sea.

We do this with multiple approaches such as combining imaging, robotics, and algorithms and integrating data analysis so that we can accelerate discovery, answer questions and help people discover new life.

That has led to us developing different technologies, such as imaging systems like EyeRIS and new types of vehicles. We’re also focused on engaging large-scale audiences and communities in this ocean life discovery process through a game called FathomVerse, which currently has over 60,000 downloads and has a player base representing 191 countries.

Your team recently released some new research related to studying deep-sea octopuses. How did you accomplish this?

A couple of years ago, we had the opportunity to go to Davidson Seamount, and there was a newly discovered site there called Octopus Garden. It provided an opportunity for us to address some big challenges with one of our colleagues at MBARI, octopus biologist Christine Huffard. With a remotely operated vehicle dive, we were able to amass an incredible data set that gave us quantitative measurements for how these animals were moving, and specifically how they were crawling over rough topography.

[Image] MBARI’s innovative EyeRIS camera system collects near real-time three-dimensional visual data about the structure and biomechanics of marine life. Pictured here filming deep-sea pearl octopus (Muusoctopus robustus). Credit: © 2022 MBARI

If you looked at available literature, there was no similar information that could inform not only octopuses’ behavior and biomechanics, but ultimately soft robots that are inspired by octopuses. It is an exciting opportunity to be a part of that and witness a large contribution to a field that’s very popular — soft robotics and octopus-inspired locomotion. It was a great opportunity, and I was excited to see our research come out in Nature this month.

What are some of the biggest challenges you’ve faced in your career?

We’re sending instruments into a very hostile environment. We’re dealing with massive pressures, saltwater, and cold temperatures — there are so many things that make working in the ocean difficult and inaccessible.

Personally, I’ve been increasingly focused on improving and increasing access so we can do scientific inquiry and welcome more people into the space so they can learn from or be inspired by it. The Bioinspiration Lab has created the Deep Ocean Inspiration Group, and it invites researchers who are interested in studying life in the ocean to utilize our data or instruments.

Recently, we’ve been focusing on one of the biggest bottlenecks our community is dealing with — it’s one thing to get access to a place, but it’s another thing to glean understanding from those observations. I’ve collected hundreds of thousands of hours of visual data from dives and operations, but only a small fraction of the data has been looked at, annotated, or shared. A lot of data for ocean life is protected behind institutional firewalls, and you hear about how we’ve mapped more of the moon than the seafloor, and that we don’t know very much about the ocean. We have actually amassed an incredible amount of data, but we don’t have a straightforward way to analyze, share, and glean understanding from it. We’re pushing for open data and easy access, and the FathomVerse platform has been key by allowing anyone with a device to participate in ocean exploration and discovery.

And what are some of the most fulfilling moments of your career?

I remember the first time we deployed an instrument called DeepPIV. It’s a laser-based illumination system, and we were working with Bruce Robison, a senior scientist at MBARI and midwater ecology expert. He has seen things that most people on the planet would never even imagine. I remember the first time we deployed DeepPIV during one of these expeditions, we turned on the laser and did a scan of a giant larvacean. We were in the control room with the ROV pilots, and Bruce was sitting behind me while I was operating the instrument. I heard him — this distinguished researcher who has seen almost everything — oohing and aahing in the background as we were doing these passes. That was so rewarding.

Another example is very recent. MBARI hosted our annual open house and our group, along with the FathomVerse team, had a little booth. A couple of our players who were “Denizens of the Deep” that had reached the top level and were active in our Discord community showed up and said hello to the team. One Denizen said that their family organized an entire trip around coming to Monterey so they could go to the MBARI Open House and the Monterey Bay Aquarium. It has changed their life and changed the direction they want to take — they’re now focusing on marine biology. That was a big highlight for me.

What kind of advice do you pass on to students or young researchers?

The first piece of advice is to be true to your interests or your passions. At a young age we tend to be told, “Oh, this isn’t interesting,” or “This isn’t something someone like you should do.” In reality, that’s a decision for you to make.

If I look back at my career, I started out in aerospace largely because I wanted to have a job at the end of undergraduate school, but if I look at my trajectory now, I’m doing what I dreamed about — participating in the discovery of life — in a place different than I originally intended. It makes sense to keep that in the back of your head and strive towards a long-term goal.

The second big piece of advice is to actively seek mentorship because you don’t know everything. And in my experience — especially when I’ve been mentoring interns — there’s a big difference between students who are successful and those who aren’t. The ones who are successful are the ones who ask questions, engage people, and seek advice from many different folks.

Where do you see yourself in five years?

I want to see FathomVerse players discovering new life in the ocean, and I think I know how we can do that. It’s such a fun and engaging thing — inviting anyone to discover ocean life.

What are some of your hobbies when you’re not working?

A lot of things! I live on the beautiful central coast of California and Big Sur is basically outside my back door. I spend as much time as I can in nature — hiking, biking, and paddling. For me, that’s the best way to unwind.

The other thing I do is get involved in my local community. I feel strongly about effecting change around me because that’s where you can have the most impact. I’m the president of the Carmel Valley Village Improvement Committee, a nonprofit organization that focuses on improving infrastructure, beautification, safety, and building community.

I’m also passionate about transportation policy — it’s something we need to make improvements in.

Is there anything else you’d like to share?

A personal driver is the idea of exploration before exploitation. The ocean is facing several challenges and pressures, and MBARI strives to acquire and share information that can guide decision-making around how we use and interact with the ocean. That’s an important motivator for everything we do.

Message sent

Thank you for sharing.