Brynn Devine, Ph.D. is an Arctic Fisheries Scientist with Oceans North, where she works on sustainable fisheries management and the conservation of Arctic marine ecosystems. The Moore Foundation has partnered with Oceans North for several years, supporting their work to protect ocean ecosystems and improve stewardship of these vulnerable areas.

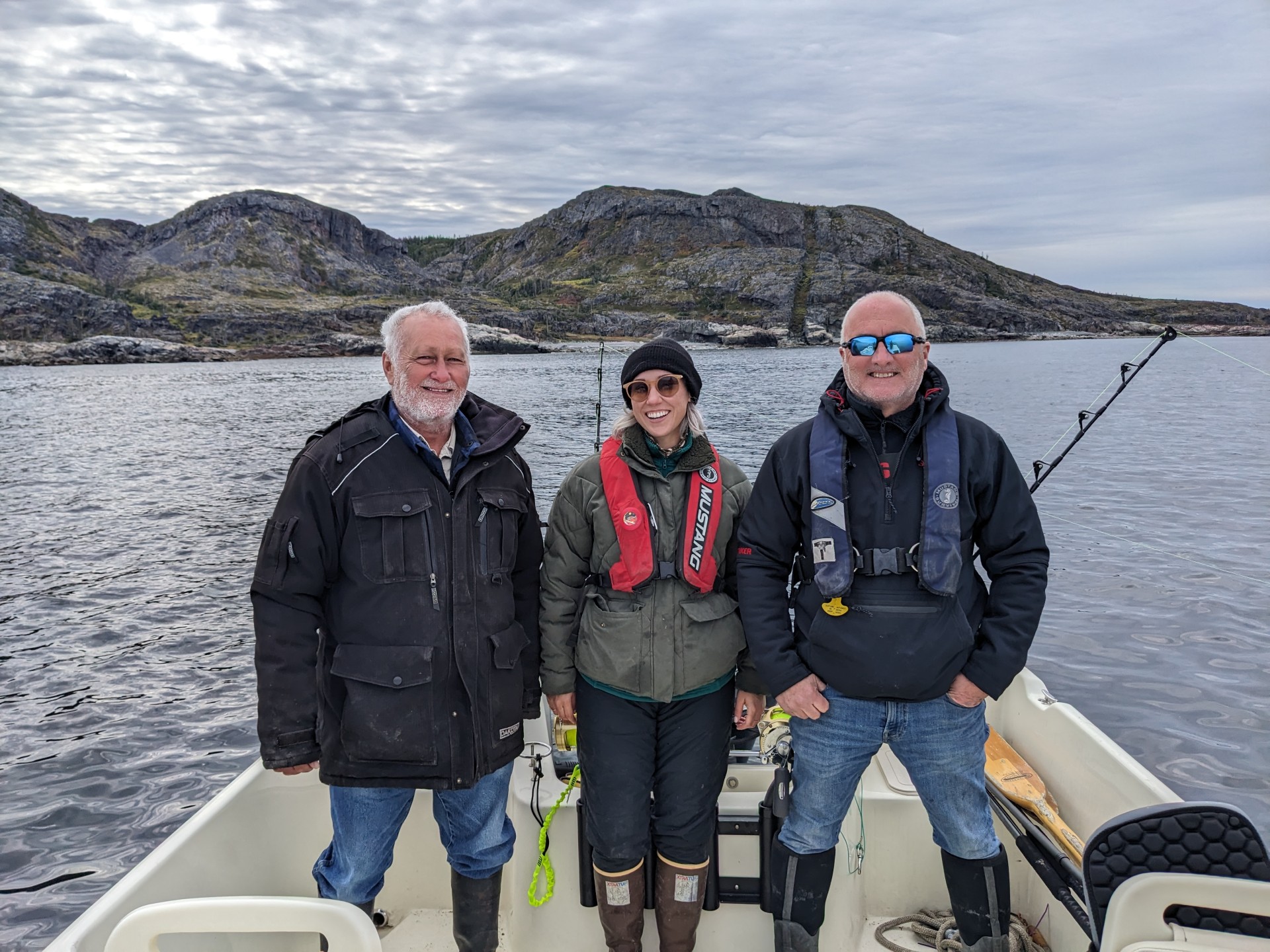

Brynn Devine. Credit: Laura Wheeland

Brynn Devine. Credit: Laura Wheeland

In this edition of Beyond the Lab, Brynn discusses her sources of inspiration and the importance of working closely with Indigenous communities in the Arctic.

What made you want to become a researcher in the first place?

I’ve always been obsessed with the natural world, and especially oceans. It probably started with the classic charismatic megafauna that often lures us in, but that quickly evolved into a very particular love of creepy, bizarre deep-sea fishes, which I still cannot get enough of.

Once you’re really interested in something, it’s only natural to start asking questions. From there, you decide whether you want to be an active participant in trying to answer those questions. For me, there was really no doubt. I wanted to know more about fishes and why they do the things they do.

What have been some of your sources of inspiration over the years?

Growing up, my parents are animal and nature lovers, and being raised in a household that really respected and enjoyed nature made a big difference. I’m grateful that they fostered that interest and allowed it to evolve. I have fond memories of going to the beach, fishing, visiting zoos and aquariums, and they always made sure we had access to resources, books, and experiences that helped us learn more. By the time I left high school, I already knew I wanted to do marine biology — I didn’t really see any other path forward.

In simple terms, how would you describe the problems that you and your colleagues are trying to solve right now?

We’re currently researching movement ecology, trying to learn more about how fishes use space in Arctic waters. This includes resident species like the Greenland shark, a very cold, deep-water shark found year-round in the north. It’s a species I’ve worked on for many years and a particularly beloved weirdo of mine.

We’re also expanding to look at some other species, including seasonal transient species like the porbeagle shark, which ventures into cold Arctic waters during late summer. We’re seeing changes in places like Nunatsiavut in northern Labrador, where people are encountering these sharks more frequently. We’re working with communities to figure out why this might be happening, and we’re also in the early stages of expanding this work to other migratory species like Atlantic cod and salmon. These are important food sources for Inuit communities, and they are species that have seen population changes in recent years.

Fishing in Postville, Nunatsiavut. Credit: Samantha Pilgrim

Fishing in Postville, Nunatsiavut. Credit: Samantha Pilgrim

We partner with local communities, conservation officers, and the Nunatsiavut Government for much of this work, and are expanding collaborations with researchers in academia and governments in Canada and Greenland as we broaden the scope to other species. A key tool we use is tagging fishes to track their movements and better understand how they use Arctic habitats, and this data helps communities understand what they’re seeing locally and can feed into better-informed spatial management policies and conservation efforts in the region.

Can you speak more about co-production of knowledge and working with Indigenous communities?

It’s paramount that these partnerships are driven by the interests of the communities. Species like cod are culturally important and valuable to the people there, and they are seeing real changes in the ecosystem. If you’ve grown up on these waters and suddenly start seeing sharks every summer where you never did before, that understandably raises a lot of questions.

That’s why it’s so important that projects are co-developed and community led. None of this work could happen without our partnerships with local governments and community members as their insight and knowledge really drives the project forward.

What have been some of the biggest challenges and most fulfilling moments of your career so far?

There are plenty of challenges. We work with highly migratory, deep-water species in harsh environments using very expensive remote technologies — so a lot can go wrong. Fieldwork always comes with challenges, especially in the Arctic, where weather, sea ice, and accessibility can limit what you can do. We’re often tagging very large fish that aren’t easy to catch, and sometimes the tags don’t work as expected, but that’s part of the game. When you do get a good day, get good data and a clear snapshot of what these fishes have been doing over the past year, it’s incredibly rewarding and worth the challenge.

What is a typical day in the field like?

It depends on the species we’re targeting. For porbeagle sharks, we’re in the community and go out daily on a speedboat with local workers and conservation officers, looking for sharks to tag.

Porbeagle shark tagging near Postville. Credit: Samantha Pilgrim

Porbeagle shark tagging near Postville. Credit: Samantha Pilgrim

For Greenland sharks, the work often involves staying offshore on a vessel for a week at a time. It’s a lot of time on the water and a lot of time in boats, which our team loves. But fishing of course comes with its frustrations — as always, some days the fish are biting, some days they aren’t.

What kind of advice do you give to students or young researchers?

Never underestimate the value of networking. I’m fairly introverted, so networking has never been my favorite thing and not something I prioritized in grad school as much as I should have. But now, so much of the work we do wouldn’t be possible without a strong network. As painful as it can be sometimes and it may take some practice, but there’s nothing more valuable than having good contacts, colleagues, and friends in different places. You can’t do this work on your own, and having those connections can really help your projects succeed and achieve your goals.

Where do you see yourself in five years, either personally or professionally?

Five years ago, I never would have imagined being where I am now — working with the people I do, going to the places I go, and studying these incredible species. I hope that in five years I’m still being surprised by the work, and I hope we have a better grasp on what these fishes are doing and that it helps communities in a meaningful way. There is a lot of uncertainty and instability in Arctic ecosystems, so I hope we’ve answered some big questions and have been able to move on to new mysteries.

What are some of your hobbies and interests outside of work?

I love fish, and that extends to fishing — both for science and for fun. I love being outdoors, hiking or going to the beach, and Nova Scotia is a great place for that. I recently took up roller skating and am trying (and mostly succeeding) not to fall. And in Canada you always need some good winter crafts to pass the time indoors, so I’ve also started knitting again.

Is there anything else you’d like to share?

I’d like to reiterate that this work is part of a much larger team effort. We’re expanding tracking work that started with sharks to many other species, and none of it would be possible without my amazing coworkers, collaborators across institutions and networks, and — most importantly — the support of local communities and governments, including our partnership with the Nunatsiavut Government. The willingness of people to share their knowledge and insight is absolutely essential. I’m incredibly grateful for that support and for being part of such a strong team.

Message sent

Thank you for sharing.